Single reed mouthpiece anatomy

Mouthpieces for clarinets & saxophones

A single reed mouthpiece has many features which affect response, timbre & intonation.

There seems to be a bewildering amount of choice and it is difficult to identify what you really need.

This article attempts to help you identify specific features which are part of mouthpiece design.

There will be a further article about how to choose a mouthpiece using a problem solving approach.

This article lists the physical characteristics for reference.

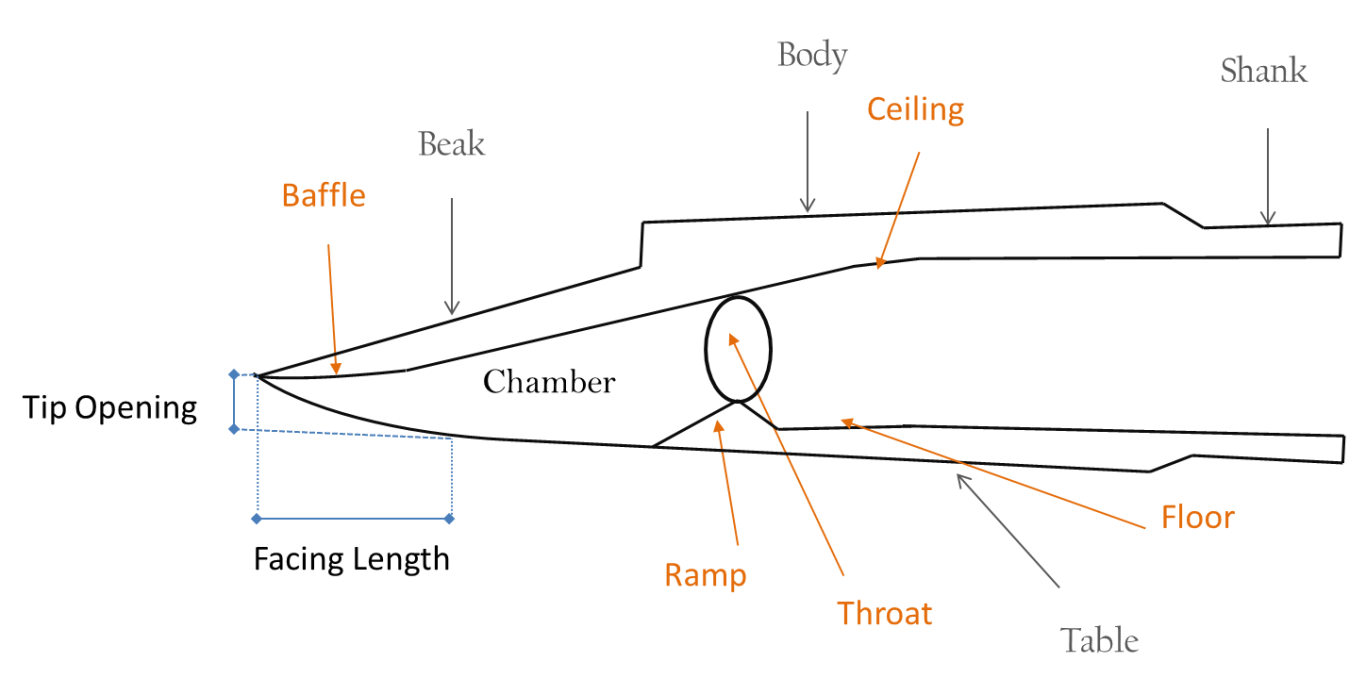

Side cutaway

Grey text and arrows are external features.

Orange text and arrows are internal features.

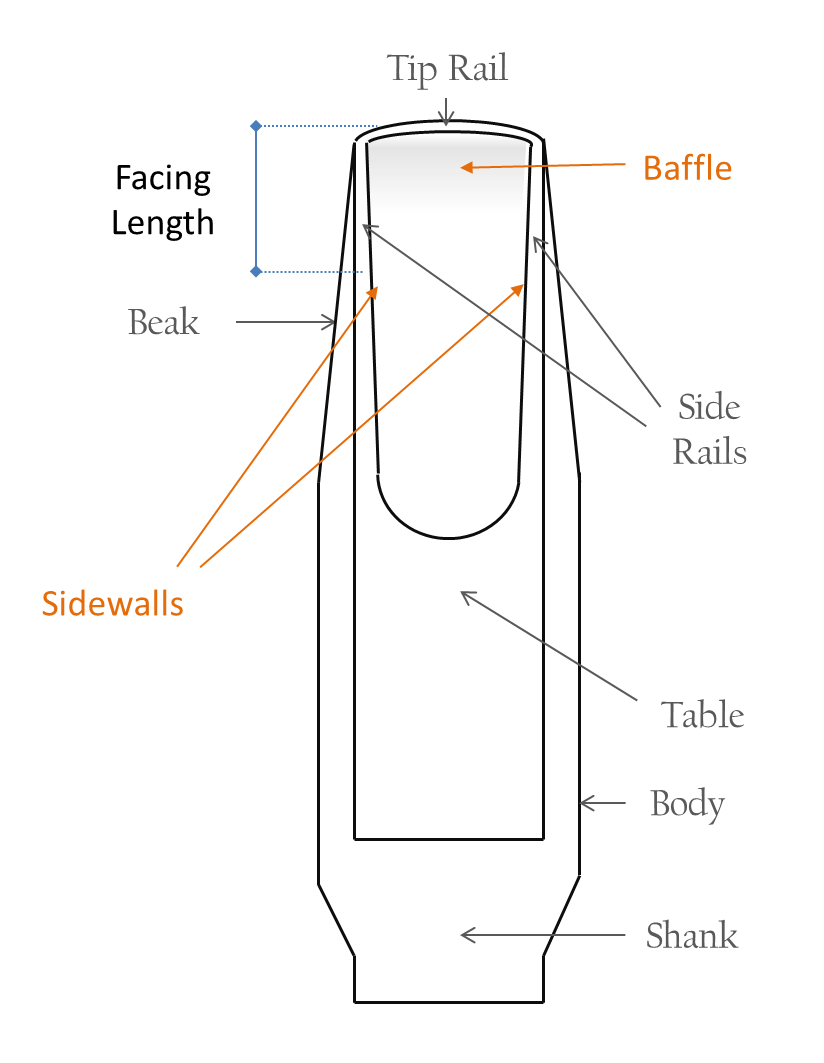

View from underneath

Most important features

Chamber

The size of the chamber (the internal volume of the mouthpiece) affects the intonation of the instrument. It also affects timbre. You should never sacrifice intonation for timbre. No-one will care how good you sound if you are out of tune! In fact, if your intonation is good, you will sound good by default.

Your instrument will work well with a limited range of chamber sizes. My observation is that modern instruments tend to work better with medium-small mouthpieces. Vintage instruments (pre 1955) tend to work better with medium.

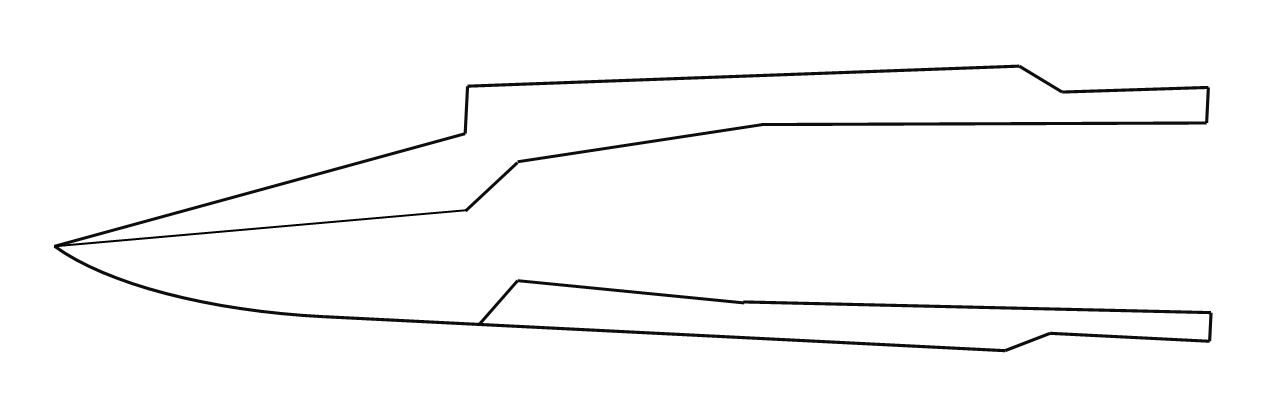

A small chamber can be defined as: High and long baffle, a high ramp with a small opening at the throat. If you put your finger in to the chamber from the beak end – there will not be much wiggle room.

Small chamber side cutaway

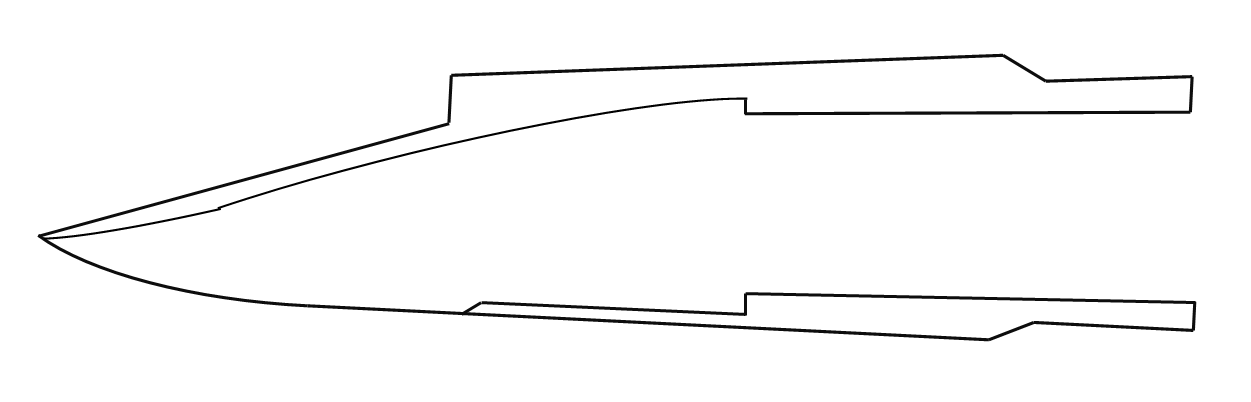

A large chamber can be defined as: Short or no visible baffle, the chamber is larger than the bore.

A larger chamber needs more air otherwise the sound produced will be weak and undefined. A softer reed or lower tip opening may be needed.

Large chamber side cutaway

A small chamber mouthpiece will not need to be pushed on to the neck far. It may cause the high pitches to be flat. A large chamber mouthpiece will need to be pushed on further which cause the high pitches to be sharp. Observe the intonation tendencies using an accurate tuner as you practice.

Altering the pitch can be done by closing the throat and raising the tongue a little. You may find this takes a while to learn and can be tiring if the physical changes for certain notes are large. Small changes to voicing are quite normal to make slight pitch corrections.

Intonation issues caused by a mismatched chamber can also be helped by changing the reed strength or using a different tip opening.

- To sharpen: Use a harder reed and/or a larger tip opening. Use more air.

- To flatten: Use a softer reed and/or a lower tip opening. Use less air.

Tip Opening

For jazz players there is an old saying: “use the biggest tip opening you can”. There is a truth to this however, there are limits. An over-large tip opening will create coarseness in the timbre (more distortion). This might be exactly the sound you want! A large tip opening will affect intonation too.

Larger tip openings allow the reed to vibrate fully allowing more overtones to be produced. The player will perceive an increase in the size or loudness of the sound. Subtone effects are easier with larger tip opening using a reed which is slightly too hard. Low notes are easier with larger tip openings and small leaks can be ‘blown’ past with a bit of physical effort.

I would change the old saying to “use the biggest tip opening you can - with a medium strength reed and good intonation”.

Facing Length

This is the distance from the tip where the facing curve starts. It is either expressed as the exact point where it starts (which is hard to measure). Or as where it starts using a 0.002” (0.5mm) feeler gauge (which is easier to measure).

There is a tendency almost manufacturers to have the same facing curve for all tip openings. As a result, large tip openings tend to have long facing lengths and small tip openings tend to have short facing lengths.

A shorter facing curve will have better intonation but more resistance. A longer facing will respond quickly but may be more difficult to control. In the worst case, a very long facing curve will cause gagging if it needs to be put in the mouth too far!

Shorter facing curves will need softer reeds.

It is best to think of tip opening and face as a combination.

A wide tip opening with a short face and soft reed may produce similar results to a narrow tip, long face and hard reed but require different embouchure pressure and lip placement.

Facing Curve

There are two broad types of facing curve; perfect curve and compound curve. French designed mouthpieces tend to use a perfect curve. American designs tend to use a compound curve.

The main difference for the player is that the American design has a slightly longer facing length which allows a greater area of the reed to vibrate and gives the timbre more body and warmth. There is also more perceivable loudness for the same tip opening with the American facing curve.

French facing curves tend to be more resistant to blowing because of the shorter facing length and suit free-blowing saxophones well.

External Features

Material

The material does not have much of an impact on timbre. Metal mouthpieces can be made more narrow and to higher tolerances (which is why they sound brighter - its because they are working properly).

Modern CNC (computer navigated cutting) machining on any type of material produces consistent results. There is nothing wrong with using plastic. Avoid metal mouthpieces if you are planning to play outdoors in winter. Avoid silver plate mouthpieces if you have an allergy to silver.

Body

The body should accommodate a ligature easily. A lot of problems are caused by a poor fitting ligature. It may be difficult to find a good fitting ligature if the body is too large or too small.

Shank and Bore

The mouthpiece should fit onto the neck easily.

If the bore is too narrow, use sandpaper on the cork. If the bore is too wide and the mouthpiece is loose, use tape to add width to the cork, or replace the cork. If you are planning to use the mouthpiece on different instruments – you can sand the bore so it is larger. Sometimes a metal ring is added to the end. This adds some mass to the mouthpiece and helps prevent the end from cracking.

Beak

The width and height of the beak greatly affect comfort and how much embouchure pressure you can apply. A beak which is too wide may feel uncomfortable, too narrow will be tiring to use. The height of the beak is helpful in making sure the top teeth are just resting on the mouthpiece and the top lip is applying pressure. If you find that you bite the mouthpiece, adding a patch or using a higher beak will help solve the problem. A higher beak will also have the effect of opening the mouth further making the oral cavity larger. This slows the air down which helps generate a warmer timbre.

Examples:

- Wide – Bari Woodwind Hard Rubber, Otto link Tone Edge

- Narrow – Berg Larsen Stainless Steel

- High – Vandoren V16 Hard Rubber, Brillhart Ebolin

- Low – D’Addario Select Jazz, Brillhart Level Air

Table

The table must be as flat as possible to help the reed seal. It is especially critical from the end of the facing curve backwards to the end of the window. It is not uncommon to see a tiny dip in the table to allow a wet reed to expand. This can usually be removed by sanding the table flat if there are air leaks in this area.

Side Rails

Side rails should be around 1mm for optimum performance. Thick side rails cause a slower response but are less fussy about reed placement. Narrow side rails can be the cause of squeaks as the reed cannot seal properly.

Tip Rail

The tip rail should be approximately half the side-rail width but no thinner than 0.5mm. The impact of small changes to the thickness of the tip rail can be huge.

A tip rail which is too thick will produce a dull sound with little projection. However, you will be able to move the reed forward and back to change its strength a little.

Internal features

Baffle

The most critical part of the mouthpiece. If the baffle angle is not correct, especially just behind the tip rail, the timbre will be stuffy, lack projection and there will be considerable resistance. Adjustments to the baffle can have dramatic results. A long high baffle reduces the overall chamber size and helps create a bright, powerful sound. Some mouthpieces have a stepped baffle. This produces an effect like the ‘loud’ button on a hi-fi. The higher partials are more present.

Sidewalls

These are either flat or scooped. Flat sidewalls help organise the air into a beam and help produce a more powerful timbre. Scooped sidewalls help increase the overall chamber size.

Ramp

A high ramp will force air to move upwards causing a bit of resistance and increasing mid-range frequencies. A mouthpiece which creates a ‘honk’ may need this area reducing or at least smoothing out if it is a vertical cut with no shaping.

Throat

The size of the throat has an impact on the power and definition of the sound produced. The shape has minimal impact (the hole in the neck is round). Larger throats allow a full range of frequencies to be produced but can sound a little soft or undefined.

Ceiling

A higher ceiling helps promote lower and higher frequencies at the expense of definition.

Floor

A lower floor helps promote lower frequencies at the expense of definition. A higher floor helps produce a powerful sound but it can sound too focussed and lacking expression.

Testing a mouthpiece for quality

The suck test

This test gives an indication that the mouthpiece is in good order.

- Put your moist reed and ligature on the mouthpiece.

- Block the shank with the palm of your hand.

- Suck the end you normally blow into - hard.

- Remove mouth – the reed should stay stuck to the facing curve for about 2 seconds. Eventually it will unstick with a satisfying pop.

If it does not;

- the reed is too hard,

- the table is not flat,

- the facing curve is not equal,

- the rails or tip rail are too thin.

Facing curve test

If you slide a piece of paper between the reed and the face of the mouthpiece, it should stop at the same point on both sides. If it does not, remove the reed, put the mouthpiece on a flat surface and try again. If the paper does not stop at the same point on both sides the mouthpiece is faulty. It may be possible to sand the table on a flat surface to get the breaking point equal if the difference is very small.

Tips

- Accept the risk that a new mouthpiece may not work for you. You will not play better unless you practice, listen to yourself and the feedback from others.

- Make sure your instrument is leak free and in good order.

- Use a new reed when testing for the first time.

- If a manufacturer uses CNC machining, the mouthpieces should be consistent. Beware of long produced mouthpieces – the tooling does wear out eventually causing inconsistency.

- Hand finished does not indicate quality – everyone has bad days or lack of time. The price will indicate how much time has been spent hand working mouthpiece.

- Ask the shop if they have a mouthpiece technician who can check and alter the mouthpiece before sending it to you. It is worth paying extra for this service.

- By all means - try an open mouthpiece but be mindful of intonation.

- If you need to use a lot of physical effort to play, how tired would you be after a 2 hour performance plus packing up and travelling? Choose a setup which is not too physically demanding.

- No biting! Use a patch.

- Record yourself often – hear how you sound from the listeners’ perspective. You may think you are producing a sound the honkasaurus would be proud of but it may be exactly what you want at the back of the room.

- If you play with good intonation - you will sound good. Play long tones with a tuner. Know how to alter your voicing to play in tune with those around you.

- Look after your reeds – these have a big impact on your sound.

- Give yourself at least 3 months to get used to your new mouthpiece.

- Your mouthpiece should always pass the suck test.

- You can make your own adjustments to mouthpieces but practice on junk mouthpieces first. The results can be astonishing.

Good upgrade mouthpieces - based on personal experience

Tenor Saxophone

Syos Steady 6 – All the dials set to medium. Works well in any situation and on almost any sax of any era.

Jody Jazz Jet 6 – Works well on modern student and intermediate horns. Has a tiny chamber and long high baffle. Is not as bright as you think it should be.

Otto Link Tone Edge 6 – Largest chamber. Always have these checked over – it is worth paying a bit extra for this service. Can have good projection after being adjusted.

Alto Saxophone

Vandoren V16 A5M – Everything set to medium.

Jody Jazz Jet 5 – Small chamber

Further Reading

The art of Saxophone Playing – Larry Teal ISBN 978-0-87487-057-2 (Alfred) ITS A BOOK! Like the internet but no electric required.

Theo Wanne resources and museum are well written and a useful read.

Jody Jazz facing charts are very helpful in comparing different sizes since there is no consistency between manufacturers.

Vandoren list of mouthpiece tip openings and suitable reeds. Very useful to find a reed strength.

Duncan Saunders 16-Oct-2024

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.